My MFA Reading List (it's not boring, I swear!)

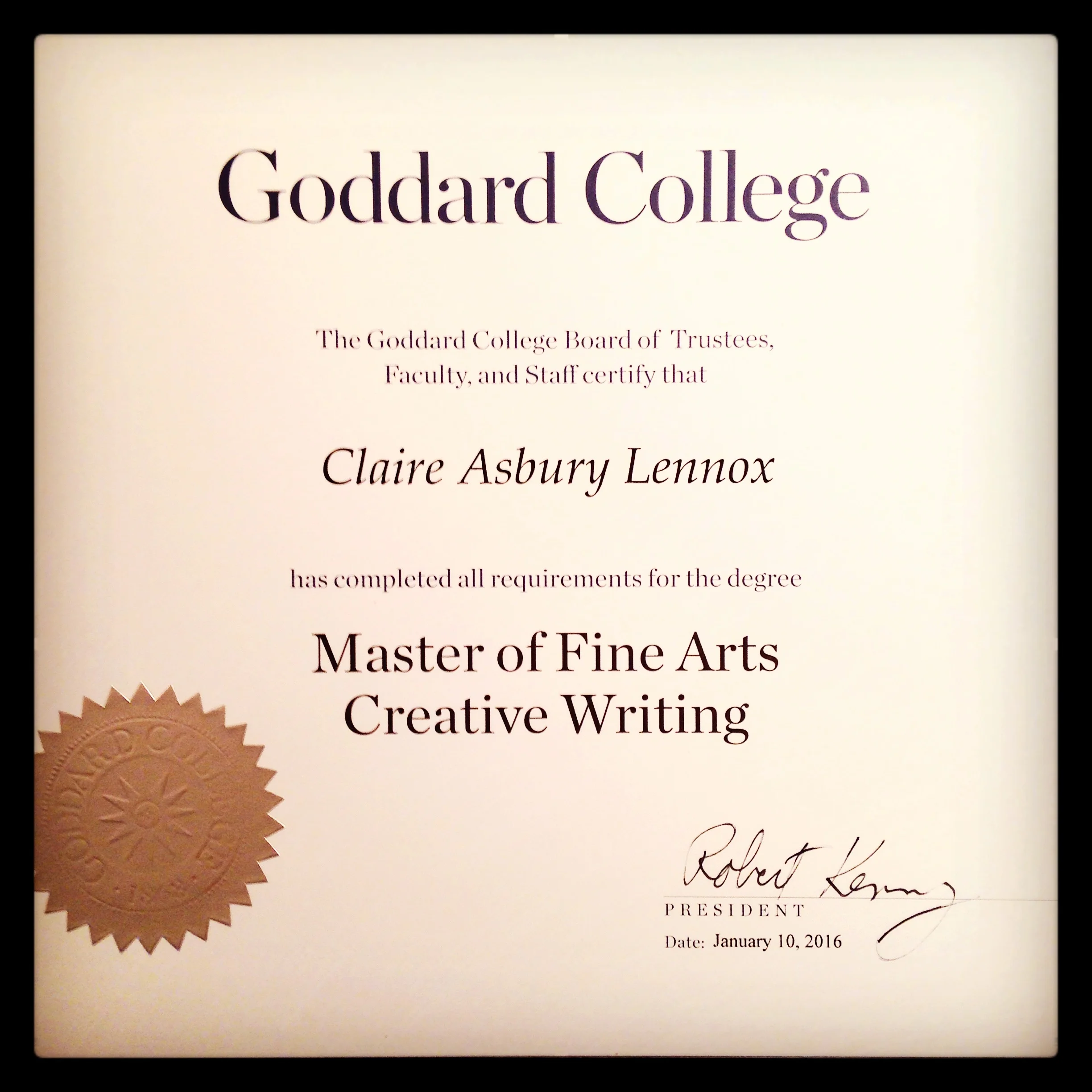

Okay, maybe it's a little boring, but enough of you have expressed interest in what I read during my MFA program in creative writing at Goddard College for me to actually give you a list! As you'll see, the books ran the gamut, from classics to contemporary, fiction to nonfiction, critical to popular. About half of these were recommended by professors and peers early in my program, while I selected the other half as I grew more certain about what I was writing and what I needed to strengthen that (i.e. books about home, belonging, etc.).

My curriculum also required that I present an annotated bibliography, writing descriptions of the books that had the greatest impact on me and why. You'll find those in bold below, and you'll find the annotations themselves underneath this looooong list. (Who doesn't like a colorful graphic to start their Monday morning?)

Here are just some of the books I most enjoyed and that deeply impacted my own writing and exploration. I'd love to hear your thoughts if you've read them (or any on the above list), or if you read them in the future!

Berry, Wendell. Jayber Crow. Jayber Crow tells his life’s story: losing his parents as a child, his many years as the barber in the small town of Port William, Kentucky, his feelings for the always-married Mattie, and his ever-shifting strands of connection to home and place. As I have explored my own thoughts and feelings about what home means and where it is, Berry’s reflective and spiritual take on place and belonging has been a guide for me.

de Waal, Edmund. The Hare With Amber Eyes: A Hidden Inheritance. de Waal, an internationally renowned potter, goes in search of his ancestors through a precious family heirloom, a collection of Japanese netsuke figurines. As he traces how the netsuke came to be in his family and the story of each generation that passed them down, he uncovers the painful story of his relatives’ escape from the Nazi Occupation in Vienna. de Waal writes the memoir as an explorer as naïve as his readers; he is learning as he goes, and shares his gathered information along the way. I too feel like I have been an explorer rather than a recollector in this writing journey, processing events through writing since they have happened so recently.

Dickens, Charles. David Copperfield. David Copperfield tells his life’s story chronologically, from beginning to the present day, all the while knowing where he has ended up, and with whom – yet never giving anything away to the reader. As someone writing a coming of age story – in a certain chunk of time, but still – I found this one of the most important books that I read during G1. Dickens’ attention to detail while being able to move the plot forward, bringing characters in and out of the narrative, and maintaining a solid voice for his protagonist, all provided takeaways for me as I began my memoir.

L’Engle, Madeleine. A Ring of Endless Light: The Austin Family Chronicles, Book 4. L’Engle writes about the Austin family, with teenage Vicky narrating about the summer they spend on the coast with their grandfather who is suffering from a terminal illness. I was drawn to this book for multiple reasons: first, because it is what I’ve begun to think of as a “quiet book,” because it deals with ordinary life in a powerful way. My book is a quiet book, and I appreciate being surrounded by others suck as L’Engle’s. Vicky’s organic narration is fluid and believable, and she isn’t afraid to ask questions. I also appreciated how the book addresses mysteries of faith and spirituality, but not in a hackneyed way.

hooks, bell. Belonging: A Culture of Place. Recommended to me by a Goddard classmate, hooks’ book of essays about home and place deeply resonated with me on some levels – she writes about her decision to return to her home state after many years away, and the positive and negative repercussions of this active choice. But it also allowed me to look through the lens of home and place through the eyes of an African American woman whose home state has a history of deep racism, like the rest of the American South. I too am from the South, but as a white woman, examining the questions of belonging through hooks’ eyes widened my view.

Julavits, Heidi. The Folded Clock: A Diary. Julavits keeps a diary – structured non-chronologically – for two years in her mid-forties, taking ordinary life events and digging into them so deeply that she comes out on the other side of every entry with a commentary on her internal self or an element of society. Julavits’ voice is wonderfully self-deprecating and unapologetic in every topic she discusses, and I was especially drawn to the way she is able to describe the anxieties and worries that she feels about certain things in her life. As someone who often overthinks the smallest things, and whose overthinking is an active part of my memoir, reading Julavits was a great inspiration.

Manguso, Sarah. Ongoingness: The End of a Diary. Sarah Manguso writes about her obsession with keeping a diary for the first half of her life, and how having her first child changes her need to record everything that happens. As with Julavits, I identified so deeply with Manguso’s intense desire to record and her idea that if it isn’t recorded, it didn’t happen. I also was drawn to her non-ending, cutting off the memoir in the middle of a sentence. Since my memoir covers a period of time that is, in a sense, ongoing, reading this book made me examine how I should end something that hasn’t ended off the page.

McCarthy, Mary. Memories of a Catholic Girlhood. Mary McCarthy’s memoir about her orphan childhood and Catholic school days fascinated me for one primary reason: after every chapter, with all its colorful detail, description and certainty, comes an “interchapter,” where McCarthy tells the reader what she made up and what she didn’t. She seems to have no qualms about fictionalizing parts of her past – typically when she doesn’t remember specifics – and then almost delights in explaining the true and false. It’s a way of writing memoir (and written before memoirs became popular) that I hadn’t considered before.

Robinson, Marilyne. Gilead. Robinson’s classic is told through the eyes, ears, and words of Rev. John Ames, an old man writing a letter to his young son. This was another “quiet book” that I found powerful because Ames is such an engaging, conflicted narrator, who describes his world, both internal and external, in such vivid detail. I got to hear Robinson speak during the week that I read Gilead, and listening to her offer some of her opinions and values in person doubled the strength of the book.

Shadid, Anthony. House of Stone: A Memoir of Home, Family, and a Lost Middle East. New York Times journalist Anthony Shadid returns to his family’s home country of Lebanon to rebuild his ancestors’ house during years of constant war. I loved Shadid’s ability to describe place, to anchor readers in Lebanon both culturally and, more intimately, in the house and history that he is attempting to bring new life. I also took notice of what was missing: his vague references to his divorce and his young daughter back in the States, and the epilogue by his never-mentioned second wife after Shadid’s untimely death. There was so much going on behind the scenes that he didn’t talk about.

Silber, Joan. Ideas of Heaven: A Ring of Stories. Silber’s “ring of stories” – stories that are all somehow connected in one way or another – made me think a lot about how to cover long stretches of time in a short story. In particular, the title story “Ideas of Heaven,” which I used in my long critical paper, covers more than fifteen years in just under 90 pages. It was fascinating to examine how Silber used language to stretch and condense time so fluidly so that the readers feel like they’ve traveled a long, short journey all at once.

Thomas, Abigail. Safekeeping: Some True Stories from a Life. Also recommended by a Goddard classmate, Abigail Thomas’s memoir of grief over the passing of an ex-husband is structured in vignettes, chapters that are only a couple of pages at the most. What I took from Thomas’s crisp, rich language was the way that she showed the emotion of grief rather than told about it. She described experiences, small and momentous, that brought home the sense of loss she was feeling, rather than simply stating it. Since I am dealing with grief in my own memoir, I took a lot from this book.

Ward, Jesmyn. Men We Reaped: A Memoir. I was intrigued with this book as soon as Reiko Rizzuto shared an excerpt in a workshop about structure during my G3 residency. Jesmyn Ward recounts the deaths of five young African American men in her hometown in Mississippi, including her brother Joshua. But it is the way she approaches these deaths and stories – going backwards chronologically, using her imagination to fill in the gaps of what she does not know – that really struck me, and stuck with me as I grappled with how to write about what I do not fully understand.

Wharton, Edith. The Age of Innocence. Wharton tells the story of Newland Archer, a young man at the turn of the 20th century who is torn between marrying the proper woman or the woman he is actually in love with, her foreign cousin. Archer does his duty, and spends the rest of his life paying for his appropriate choice. I was really taken with how fluidly and subtly Wharton made society a character in the novel, driving Archer’s decision and how he handles his feelings. I feel like society is, in some ways, a character in my memoir, as I wrestle with the idea that returning home as an adult is somehow a failure.

Cheers to the joys of literature! Happy Monday.